Reforestation Options for American Chestnuts

Copyright© 2019 by Go Native Tree Farm

Introduction

Before 1900, American Chestnut (Castenea dentata) was a dominant eastern North American forest species. Then an ecological disaster occurred on par with an asteroid extinction event, and four billion American Chestnuts died. The fungus Cryphonectria parasitica appeared suddenly on the trees, which almost certainly was brought by humans on chestnuts imported from Eurasia. Within a few decades, an estimated four billion chestnut trees died in the forest. A few dozen survivors are still present in scattered stands, mostly in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia. On the west coast, specimen trees still survive because the blight is not present there. Root shoots can be found in the historic range today, because the basal tissue and root stock are not always killed by the fungus. Recovery of the forest species in the native range is the topic of this essay.

There are things that you can do about it. There are three primary tactics that have been identified to help solve the problem. All are valid scientific approaches, and may best be used in tandem to ultimately restore the species. The following is a summary of the avenues that are being pursued.

Recovery Tactics

There are things that you can do about it. There are three primary tactics that have been identified to help solve the problem. All are valid scientific approaches, and may best be used in tandem to ultimately restore the species. The following is a summary of the avenues that are being pursued.

Recovery Tactics

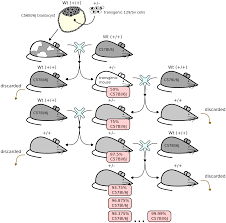

1) Back-crossing with Asian Species. The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) has been active for many years, following the technical approach of back-crossing American Chestnuts and Asian chestnuts. As of this writing, they have produced up to 15/16 Castenea dentata genome. Although this process requires many years of successional effort, it should ultimately result in a nearly pure native genome. Each generation of halving the Asian genome requires a minimum of ten to fifteen years, so the process is slow by human standards. Meanwhile, the drawbacks include the new introduction of Asian genome into the forest, plus the difficulty of obtaining a significant enough number of plants to effect a substantial effort.

2) Extreme Natural Selection. The American Chestnut Cooperator’s Foundation (ACCF) is following the approach of extreme natural selection by manually cross-pollinating the few disparate old survivors, which can be described as extreme natural selection. ACCF geneticists calculated that perhaps 10% (estimates range from 5% to 20%) of the plants produced in this manner will exhibit blight resistance at least as favorable as the parent trees. Furthermore, they believe that the progeny of these plants should all exhibit natural blight resistance. The advantage of this approach is to immediately produce potentially resistant 100% C. dentata seedlings. A drawback is the difficulty of obtaining a significant enough number of plants to effect a substantial recovery effort. More than one generation of breeding may be necessary to assure resistance.

3) Genetic Weakening of the Fungus. Another approach which may eventually prove to be essential is the development of hypo-virulent chestnut blight inoculants. This weakened form of the fungus spores has been introduced into wild populations, which has the effect of making the trees less susceptible to the blight. The weakened blight should also be helpful in protecting the Allegheny Chinkapin (Castenea pumila) from Chestnut Blight.

4) Gene Altering (GMO). This is a new technology that is being developed by a group led by Dr. William Powell at SUNY ESF. Using a gene taken from wheat, his group has successfully bred a lineage of American chestnut trees that tolerates the blight, and they hope to someday release it into the wild. The pros and cons are similar to those for backcrossing, except that the Asian genome issue has been circumvented.

The plants produced by this approach could be viewed as a new species. As such, putting them into the wild will be a potentially irreversible experiment. It is important to carefully evaluate the effects of the consequences with controlled experimental plots before the resulting plants are considered for environmental restoration. Famous books and movies have been made that seek to make this point. Sara Fitzsimmons is a researcher that works with Pennsylvania State University and The American Chestnut Foundation. She says that there are no guarantees that any single approach will prove fruitful: “You can’t say with certainty that this gene will, no matter what, restore the species.” See the chestnut GMO article in the Christian Science Monitor website for more information on this tactic

Should we bring back the American Chestnut with GMO?

It is likely that a combination of these approaches will ultimately result in recovery of the species as a forest tree.

Our Experience

We have concluded that we prefer accelerated natural selection (the ACCF approach) in the near term, since it is unclear how to remove the Asian genome from the forest once it is introduced. The weakened blight genome is likely already out in the environment, and already it may be becoming helpful. The outlook has definitely improved in recent years, due to a combination of the above research work. It is now possible to plant this species with reasonable hope for survival.

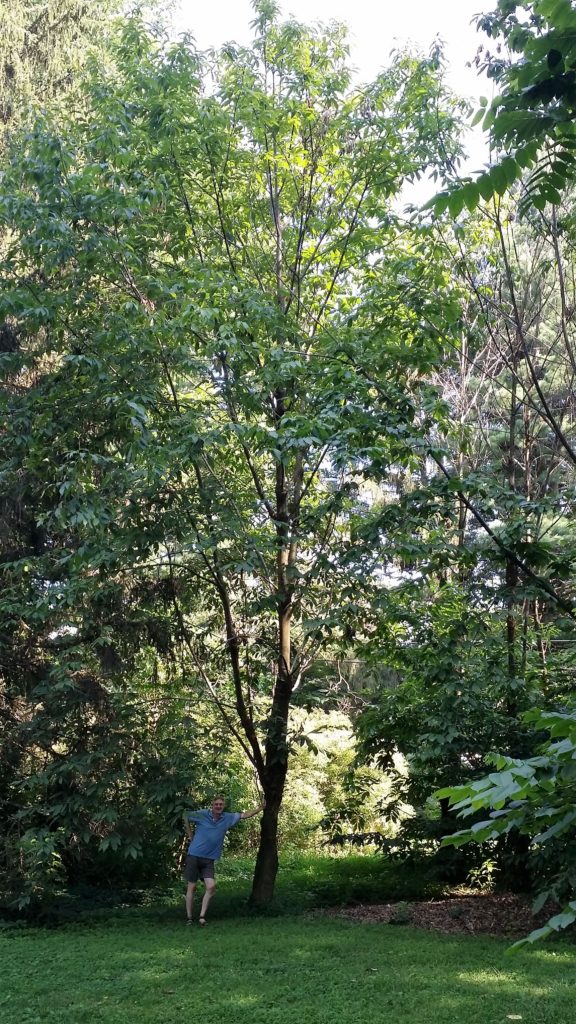

About twenty years ago, we obtained fifty manually cross-pollinated seedlings from old survivors (Tactic 2) and planted them as a recovery grove. The plants came from nuts that were collected in the year 2000. Voles ate one-third of the seedlings over the first winter, after which we surrounded each plant with 1/4 “- mesh steel screen tubes. After seven to ten years, the remaining plants had grown to nearly thirty feet in height and began to produce nuts. Now, twenty years later, about six trees still survive. They are forty to fifty feet tall and over one foot DBH. Two of them exhibit the best resistance features, i.e. minimal sprouts at the trunk base, a nicely formed crown, and no branch or crown die-off. They all have swollen burls on their trunks, but seem to be growing through it. In other words, the blight is present but the trees still survive and produce nuts each year. So if the geneticist calculations are correct, then we are most of the way through the winnowing process. We have collected up to 2000 seeds per year from the two best trees in the grove. We now collect seed from the two best plants (pictured below), so the blight resistance may be improved by as much as a factor of 2.5 billion [(40/4 billion) X (2/50)].

We offer our seedlings to recovery projects, and we can offer advice to planters to prevent animal damage and related infant mortality issues. Based on the above information, we can estimate that at least two out of three seedlings should exhibit favorable blight resistance, at least sufficient to allow plants to live for twenty years or longer. The plants are 100% American genome. Starting three to get two survivors is a big improvement from a few decades ago, when it was nearly impossible to do so. Please contact us if you have questions or wish to obtain seedlings for a recovery project.

| Latin Name | Common Name | Plant and Container Size | #On hand |

| Castenea dentata | American Chestnut | 12”, D60 cells 12-36”, 2 gal. tall | 1000 100 (Fall 2020) |

| Castenea pumila | Allegheny Chinkapin | 12-24”, 1 gal tall. | 20 |